This week, we will cover data summaries, data structure, linear regression and its assumptions.

At the beginning of each session, we will need to load our libraries, so let’s load the packages for this week.

library(tidyverse)

library(plotrix)

library(ggpubr) #install.packages("ggpubr")

library(qqplotr) #install.packages("qqplotr")

library(PerformanceAnalytics)#install.packages("PerformanceAnalytics")

library(gcookbook)

library(tidyr) #install.packages("tidyr") Sample Statistics and Summary results

Mean, variance, and error values are always required for the final report. It can take a while to sort the data in the right way, and several times you may want to check how your data looks frequently. Tydiverse is a complex group of packages that include ggplot2 and dplyr. Adding, changing, combining, removing is simple with dplyr.

data("storms")

head(storms) #look at the first 6 rows

## # A tibble: 6 x 13

## name year month day hour lat long status category wind pressure

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <ord> <int> <int>

## 1 Amy 1975 6 27 0 27.5 -79 tropical de~ -1 25 1013

## 2 Amy 1975 6 27 6 28.5 -79 tropical de~ -1 25 1013

## 3 Amy 1975 6 27 12 29.5 -79 tropical de~ -1 25 1013

## 4 Amy 1975 6 27 18 30.5 -79 tropical de~ -1 25 1013

## 5 Amy 1975 6 28 0 31.5 -78.8 tropical de~ -1 25 1012

## 6 Amy 1975 6 28 6 32.4 -78.7 tropical de~ -1 25 1012

## # ... with 2 more variables: ts_diameter <dbl>, hu_diameter <dbl>mean(storms$wind) # mean wind speed of all the recored storms

## [1] 53.495sd(storms$pressure) # pressure standard deviation of all the recored storms

## [1] 19.51678plotrix::std.error(storms$ts_diameter) # standard error of storm eye diameter

## [1] 2.394685I am sure you are familiar with that as it is something we can get from any statistical program; now, let’s look at how to deal with more information and different results.

#library(tidyverse)

storms[,c(1,2,10,11)]%>% #dataset and variables we will work with [row,column] use c(for selecting multiple columns)

dplyr::group_by(name,year)%>% #group by name and year

dplyr::summarise_all(funs(mean(.,na.rm = T), #use funs( to get multiple estimators)

sd(.),

var(.), #sd^2

plotrix::std.error(.),

observations=length(.))) # we can name the variables directly length tells you how many observations in each group

## # A tibble: 426 x 12

## # Groups: name [198]

## name year wind_mean pressure_mean wind_sd pressure_sd wind_var pressure_var

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 AL011993 1993 27.5 1000. 2.67 1.55 7.14 2.41

## 2 AL012000 2000 25 1009. 0 0.957 0 0.917

## 3 AL021992 1992 29 1007. 2.24 0.894 5 0.8

## 4 AL021994 1994 24.2 1016. 5.85 0.753 34.2 0.567

## 5 AL021999 1999 28.8 1005. 2.5 0.957 6.25 0.917

## 6 AL022000 2000 29.2 1009. 1.95 0.515 3.79 0.265

## 7 AL022001 2001 25 1011 0 0.707 0 0.5

## 8 AL022003 2003 30 1009. 0 0.957 0 0.917

## 9 AL022006 2006 38 1002. 5.70 4.04 32.5 16.3

## 10 AL031987 1987 21.2 1010. 8.71 2.44 75.8 5.97

## # ... with 416 more rows, and 4 more variables: wind_plotrix::std.error <dbl>,

## # pressure_plotrix::std.error <dbl>, wind_observations <int>,

## # pressure_observations <int>- group_by is one of the best elements of dplyr; it works by making one data set for all the information you add in group_by(). Here, we group all the storms with the same name; if there are multiple elements, then we group them again by year. In the output, you will see there is

Groups: name [198]this means that there are 198 names, some with multiple years, so we get a data set with 426 rows. - summarise_all means that all the functions will be applied to all the variables excluded from

group_by. - na.rm and ‘.’: The

.means to use all the information; we want to do it for each variable.na.rm=Tmeans remove missing values if there are some TRUE (yes).

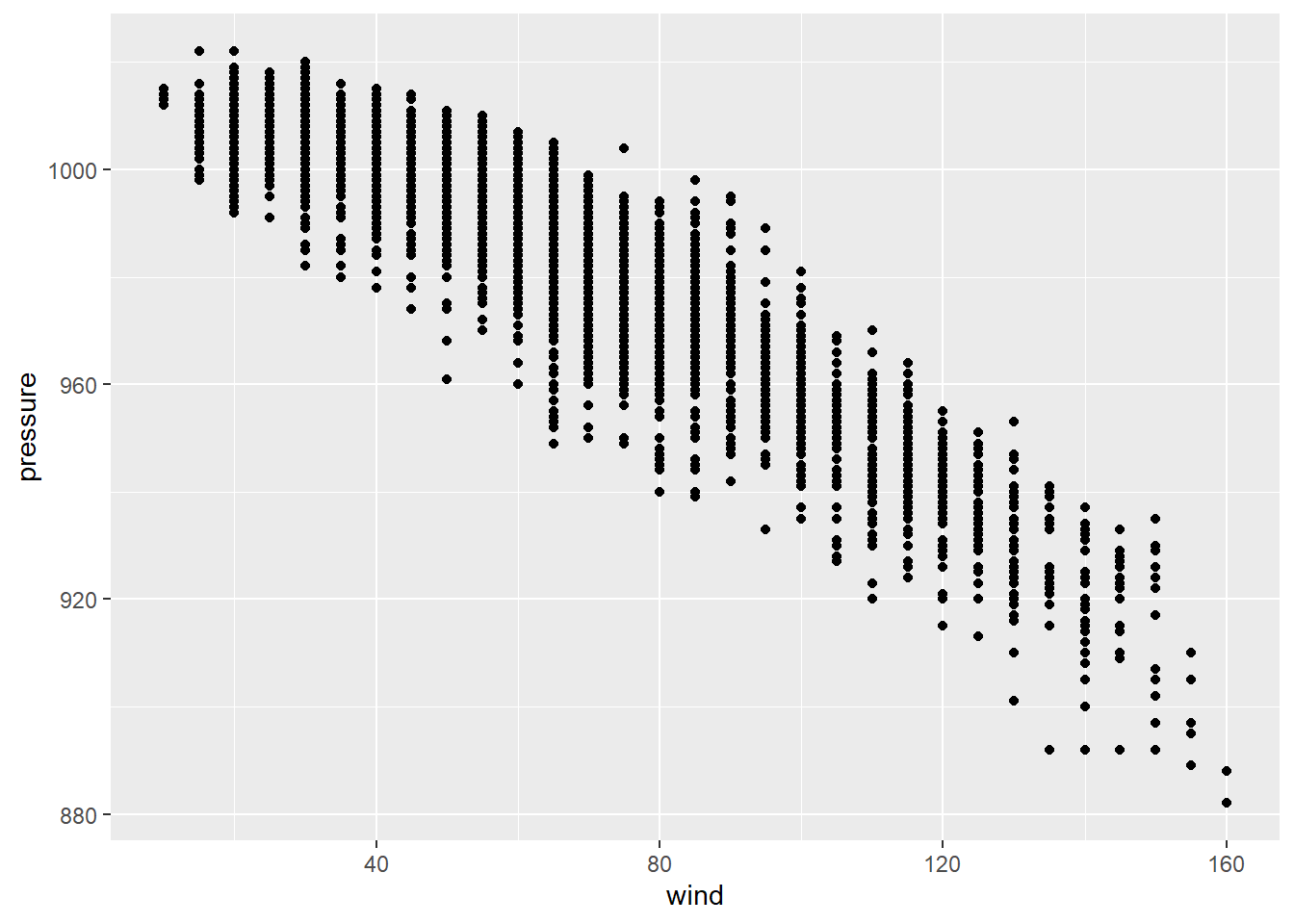

You want to know if there is a relationship between wind and pressure, so we need to visualize both variables in a scatter plot.

data("storms") #we will work with the dataset: Carbon Dioxide Uptake in Grass Plants

tail(storms,4) #show me the last 4 observations

## # A tibble: 4 x 13

## name year month day hour lat long status category wind pressure

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <ord> <int> <int>

## 1 Kate 2015 11 11 0 33.1 -71.3 hurricane 1 65 990

## 2 Kate 2015 11 11 6 35.2 -67.6 hurricane 1 70 985

## 3 Kate 2015 11 11 12 36.2 -62.5 hurricane 1 75 980

## 4 Kate 2015 11 11 18 37.6 -58.2 hurricane 1 65 980

## # ... with 2 more variables: ts_diameter <dbl>, hu_diameter <dbl>

# we will begin by plotting the variables of our hypothesisggplot(storms,mapping = aes(x=wind,y=pressure))+

geom_point()

It looks like there is some sort of relationship, a negative relationship, between our variables of interest. However, we need statistical models to determine the changes in pressure with wind and how significant are those changes.

Least squares Linear Regression:

The least-squares method, also defined as the line of best fit, aims to produce a model that reduces the variation or error between the expected and predicted values. Next, we will run a simple linear regression with lm with our two variables to understand this concept and estimate model parameters which are often called ordinary least squares estimates. The previous scatter looked roughly linear, so let’s examine their relationship.

fit.lm<-lm(pressure~wind, data = storms) # y~x makes sure to use this `~`

fit.lm #information inside fit.lm

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = pressure ~ wind, data = storms)

##

## Coefficients:

## (Intercept) wind

## 1029.6670 -0.7015Equation for the LSLR: 1029.66 - 0.7015x

We can also add the error term by using sigma.

sigma(fit.lm) # residual standard deviation E

## [1] 6.536737confint(fit.lm) # get confidence intervals for all the terms

## 2.5 % 97.5 %

## (Intercept) 1029.3759591 1029.9580714

## wind -0.7064102 -0.6966387Therefore, the equation for the LSLR with a CI of 95% confidence level will be 1029.66 - 0.7015x 6.537.

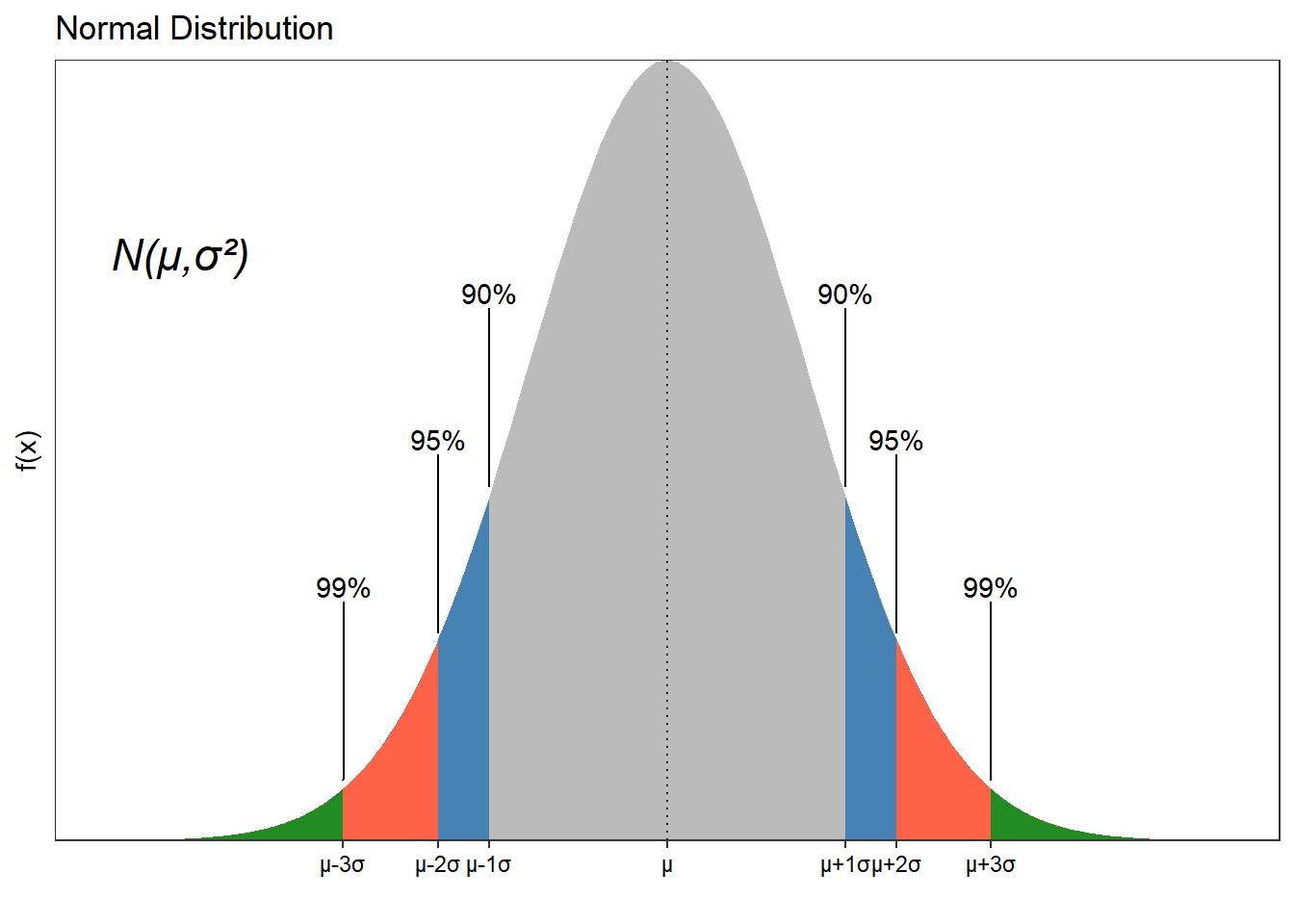

Confidence Intervals (CI)

They are values that also represent the accuracy of our sample mean. This will show a range of plausible values not only for the mean but for any unknown parameter.

labels<-data.frame(label=c("99%","95%","90%","90%","95%","99%"),

x=c(-2.326348,-1.644854,-1.281552,1.281552,1.644854,2.326348),

y=c(0.03,0.105,0.18,0.18,0.105,0.03))

ggplot(data.frame(x = c(-4, 4)), aes(x = x)) +

stat_function(fun = dnorm,

geom = "area",fill = "grey10",alpha = .3) +

geom_vline(xintercept=0,colour="black",linetype="dotted")+

stat_function(fun = dnorm,

geom = "area",fill = "steelblue",

xlim = c(-qnorm(.90), -4))+

stat_function(fun = dnorm,geom = "area",fill = "steelblue",xlim = c(qnorm(.90), 4))+

stat_function(fun = dnorm,geom = "area",fill = "tomato",xlim = c(qnorm(.95), 4))+

stat_function(fun = dnorm,geom = "area",fill = "tomato",xlim = c(-qnorm(.95), -4))+

stat_function(fun = dnorm,geom = "area",fill = "forestgreen",xlim = c(qnorm(.99), 4))+

stat_function(fun = dnorm,geom = "area",fill = "forestgreen",xlim = c(-qnorm(.99), -4))+

ggrepel::geom_text_repel(data=labels,mapping = aes(x=x,y=y,label=label),nudge_y = 0.1)+

annotate("text",x=-3.5,y=0.3,label=paste0("N(","\u03BC",",","\u03C3","\u00B2", ")"),size=6,fontface = 'italic')+

labs(title = "Normal Distribution",x ="",y = "f(x)") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(-2.326348,-1.644854,-1.281552,0,1.281552,1.644854,2.326348),

labels = c(paste0("\u03BC",c(-3,-2,-1),"\u03C3"),"\u03BC",paste0("\u03BC","\u002B",c(1,2,3),"\u03C3")))+

scale_y_continuous(expand = c(0.0,0.0))+ # no space at the top/bottom

theme_bw()+

theme(panel.grid = element_blank(), # remove grid lines

axis.text.x = element_text(colour="black"), # text of x axis black

axis.text.y =element_blank(), #remove the labels of y axis

axis.ticks.y = element_blank()) #remove the ticks on y axis only

As we increase our confidence interval, we are more likely to include the true value of the parameter.

Coefficient of determination

In our regression model, the coefficient of determination is calculated by diving the quotient of the variances of the dependent variable’s fitted and observed values. This tells us how much of the variation of y is explain by the model or how well the model fits the data. It would help to look at the adjusted R-square when fitting a multiple regression because it deals with any noise created by adding more variables.

results=base::summary(fit.lm) #save all the summary in a large summary

results$r.squared #take the coefficient of determination

## [1] 0.8878337The model explains 88.78% of the variation in pressure.

Simple Linear Regression

The regression model was done, and we needed to know how significant those results were. However, before we begin, you must check the data before regression and any other model that you run. By this, it is meant that we should determine something like the normality of the data. There are multiple tests, and if not normally distributed, we will need to transform the data.

Assumption One (Normality)

Use shapiro.test to carry out the normality test; here, the H0 means normally distributed data. P-Values >0.05 will support this normal distribution of your variable.

#library(gcookbook) #data set

library(gcookbook)

data("heightweight")

shapiro.test(heightweight$heightIn) # normality test passed

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: heightweight$heightIn

## W = 0.99628, p-value = 0.849# normality test failed

shapiro.test(iris$Sepal.Length)

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: iris$Sepal.Length

## W = 0.97609, p-value = 0.01018# normality test with transformed data passed

shapiro.test(log(iris$Sepal.Length))

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: log(iris$Sepal.Length)

## W = 0.98253, p-value = 0.05388Clearly, we can make more sense of the data when we plot it. Plotting will be helpful when you have many variables and want to have a quick look at the data.

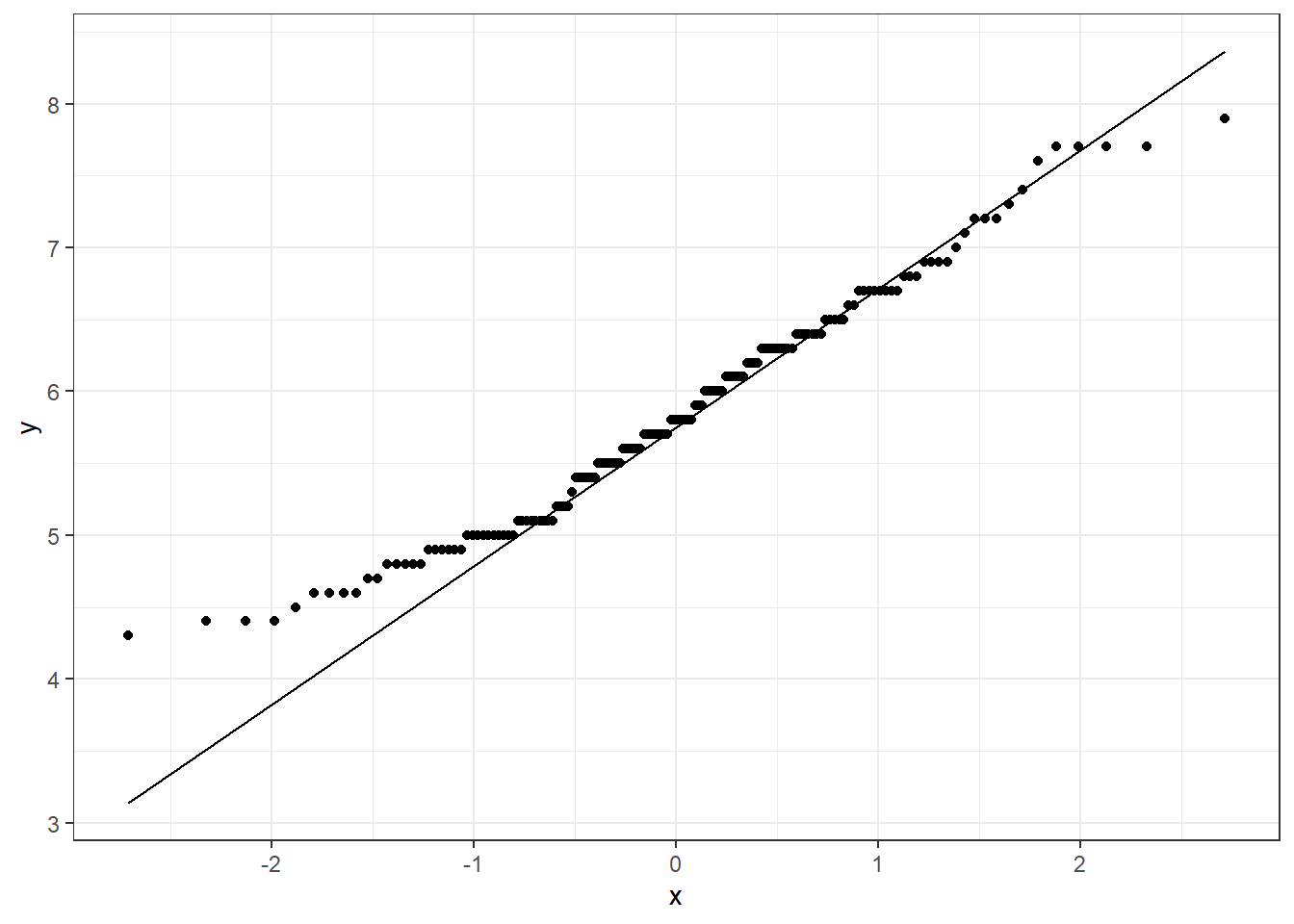

# not transformed data

ggplot(data=iris,mapping = aes(sample=Sepal.Length))+

geom_qq()+

geom_qq_line()+

theme_bw()

#plot with transformed data and an alternative package to ggplot2

ggpubr::ggqqplot(log(iris$Sepal.Length)) # set the variable that you want to get the qqplot

Data transformation resulted in a better qq-plot. Now we can see why it passed the

shapiro.test.We used two options, one plot with the normal ggplot2 and the second one with the package

ggpubr. The last is a package that reduces ggplot2 lines of code and gives you great results. It is a great option if you work with small data sets and want to have good graphs. We will cover more about this package in a few weeks.

Let’s build a data set for our regressions and model:

#library(qqplotr)

set.seed(15)

df<-data.frame(temperature=rnorm(100,mean = 25,sd=8),

wind=rnorm(100,mean = 10,sd=1.2),

radiation=rnorm(100,mean = 5000,sd=1000),

bacterias=rnorm(100,mean = 50,sd=24.22),

groups=c("Day","Night"))

head(df,6)

## temperature wind radiation bacterias groups

## 1 27.07058 9.951969 5818.690 55.49904 Day

## 2 39.64897 9.964412 4938.840 29.82846 Night

## 3 22.28305 8.550304 5527.404 38.30339 Day

## 4 32.17759 11.758406 4995.665 60.15574 Night

## 5 28.90413 11.294930 5228.475 42.19714 Day

## 6 14.95691 9.598272 3894.247 85.30897 Nightshapiro.test(df$radiation) # normal distribution

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: df$radiation

## W = 0.96947, p-value = 0.02012

shapiro.test(df$wind) # normal distribution

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: df$wind

## W = 0.97584, p-value = 0.06274

shapiro.test(df$temperature) #normal distribution

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: df$temperature

## W = 0.992, p-value = 0.8216Assumption two (Linearity)

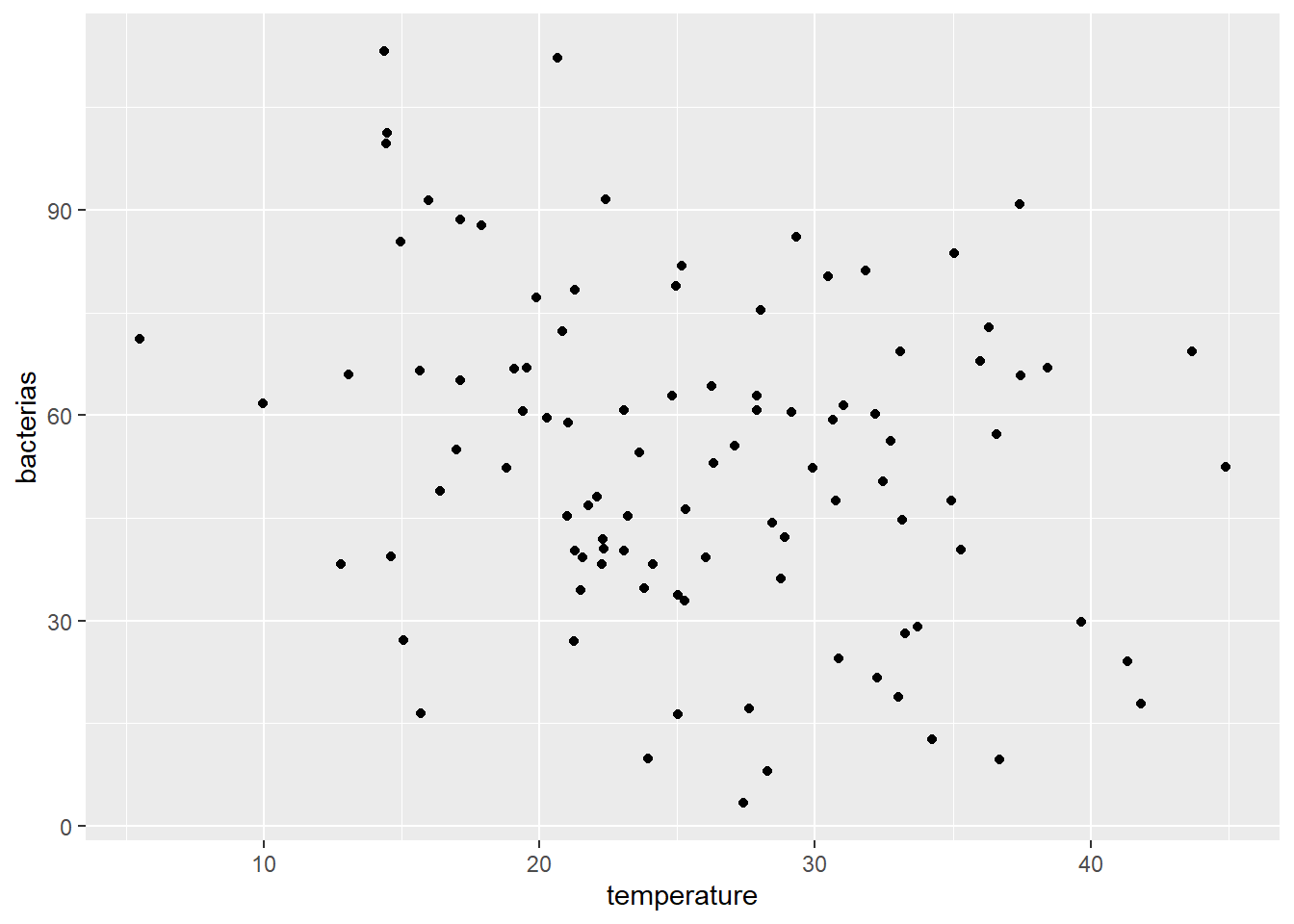

The relationship between the independent and dependent variables must be linear. A scatter plot is our alternative to test if there is a linear distribution that would show our points is something like a straight line.

ggplot(df,mapping = aes(x=temperature,y=bacterias))+

geom_point()

There is no apparent linearity, but you can see that data is showing a slightly decreasing trend.

Now that all the variables are normally distributed and there is a linear relationship, we can use them in our regression.

Null hypothesis (H0): There is no change in bacteria population with temperature, radiation, etc.

Alternative hypothesis (H1): Bacteria population changes with temperature, radiation, etc.

fit.lm<- lm(bacterias~temperature,data=df)

summary(fit.lm)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = bacterias ~ temperature, data = df)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -49.153 -16.873 1.069 16.100 54.899

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 72.4498 7.9532 9.110 1.04e-14 ***

## temperature -0.7300 0.2945 -2.478 0.0149 *

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 23.3 on 98 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.05898, Adjusted R-squared: 0.04938

## F-statistic: 6.142 on 1 and 98 DF, p-value: 0.01491Breakdown of the elements of the results summary:

The estimates

(Estimate)is the change in y caused by each element of the regression. (Intercept) or the value of the y-intercept (in this case 60.7266) is the calculated value of y when x is 0.temperature or any x variable values in theEstimatecolumn show changes in y (e.g., the population of bacteria) with one unit increase inx`. Therefore, for the temperature group, we could say that the bacteria population gets reduced by -0.22 units for each increment in temperature if Pr(>|t|) < 0.05. Here it is not the case, so we can not reach that conclusion.The standard error of the estimated values are in the second column

Std. Error.The test statistic showed under

t value.The p-value

Pr(>| t | ), the probability of finding the given t-statistic by chance, and therefore, the calculatedestimatefor that variable.

We can see that the bacteria population did not change with temperature (P-value>0.05). Let’s see how radiation affects our bacteria population.

fit.lm<- lm(bacterias~radiation,data=df)

summary(fit.lm)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = bacterias ~ radiation, data = df)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -48.910 -17.761 -0.201 13.905 58.504

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 64.030405 11.503156 5.566 2.27e-07 ***

## radiation -0.002119 0.002287 -0.927 0.356

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 23.92 on 98 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.008686, Adjusted R-squared: -0.001429

## F-statistic: 0.8587 on 1 and 98 DF, p-value: 0.3564We got similar results, so we would conclude that we are 95% confident that radiation and temperature alone do not affect the population of bacteria. 95% confident because we run our model at this CI.

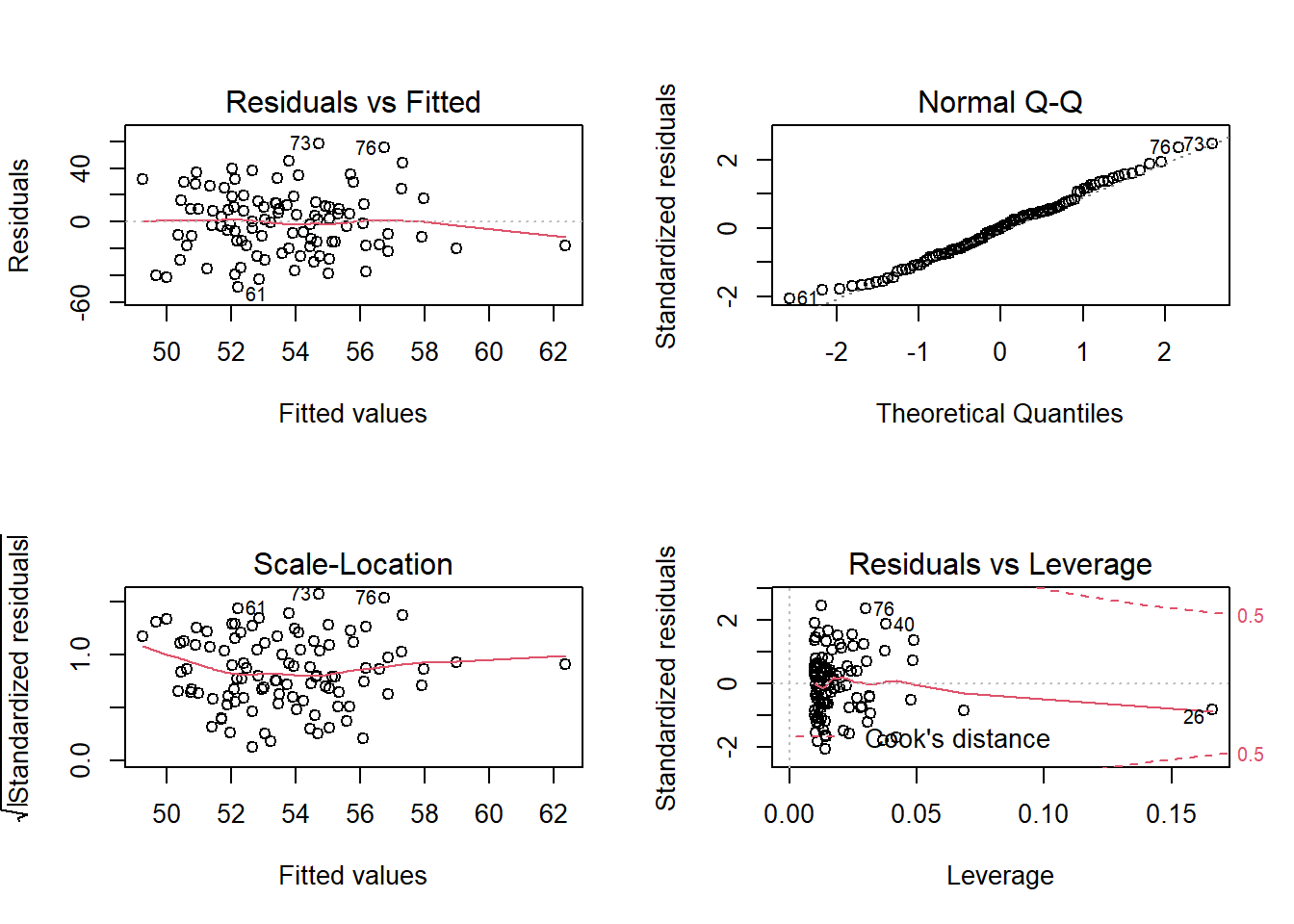

Model test assumption (Homoscedasticity)

We should ensure that the model fitted meets this last assumption, the same variance over the prediction range, to maintain the model. This means that the error term needs to be the same across all values of the independent variables. The fitted model already has all the information we need for the plots, so we will just call plot(model).

par(mfrow=c(2,2)) #plot panel to fit 2 by 2 pictures

plot(fit.lm) # lm result has 4 figures

par(mfrow=c(1,1)) #we set them back to normalHere we can see that the residual errors are constant across the groups and distributed evenly. Look at the Normal Q-Q (top right), which under homoscedasticity it should show the points along the line.

- This will conclude a simple linear regression model and its analysis.

Extra Notes

- When we get many variables, we can do the test in one line of code with lappy. Additionally, when you run multiple variables, the resulting object is a list (results of the first, results of the second, results of the n). We can’t access the list like a data frame; it needs list[[i]] to observe, export, use all those values in other parts of your documents. We need to unlist, bind rows (

rbind), and save them in adata.frame.

Run the same test for each variable

results<-data.frame(

do.call(rbind,

lapply(df[,1:3],function(x) shapiro.test(x)[c("statistic","p.value")])))

results # how the data looks like

## statistic p.value

## temperature 0.9920047 0.8215678

## wind 0.9758363 0.06274086

## radiation 0.969466 0.02012186Let’s take each element and extract just what we need.

results$statistic<-unlist(results$statistic) # remove any text left,the list structure and make it a new vector

results$p.value<-unlist(results$p.value) #remove the list structure and make it a new vector

str(results) # data frame with two numeric variables

## 'data.frame': 3 obs. of 2 variables:

## $ statistic: num 0.992 0.976 0.969

## $ p.value : num 0.8216 0.0627 0.0201Most of the time there are multiple options so you can also do something like this too:

#option 2

allshapiro.tes<-lapply(df[,1:3],shapiro.test) #as a list apply the function shapiro.test to the variables [,1:3] in the data frame df

#allshapiro.tes # how the data looks like for all the variables

results<-data.frame(t(sapply(allshapiro.tes,`[`,c("statistic","p.value")))) #let's take what we really need

results$statistic<-unlist(results$statistic) # remove any text left,the list structure and make it a new vector

results$p.value<-unlist(results$p.value) #remove the list structure and make it a new vector

str(results)

## 'data.frame': 3 obs. of 2 variables:

## $ statistic: num 0.992 0.976 0.969

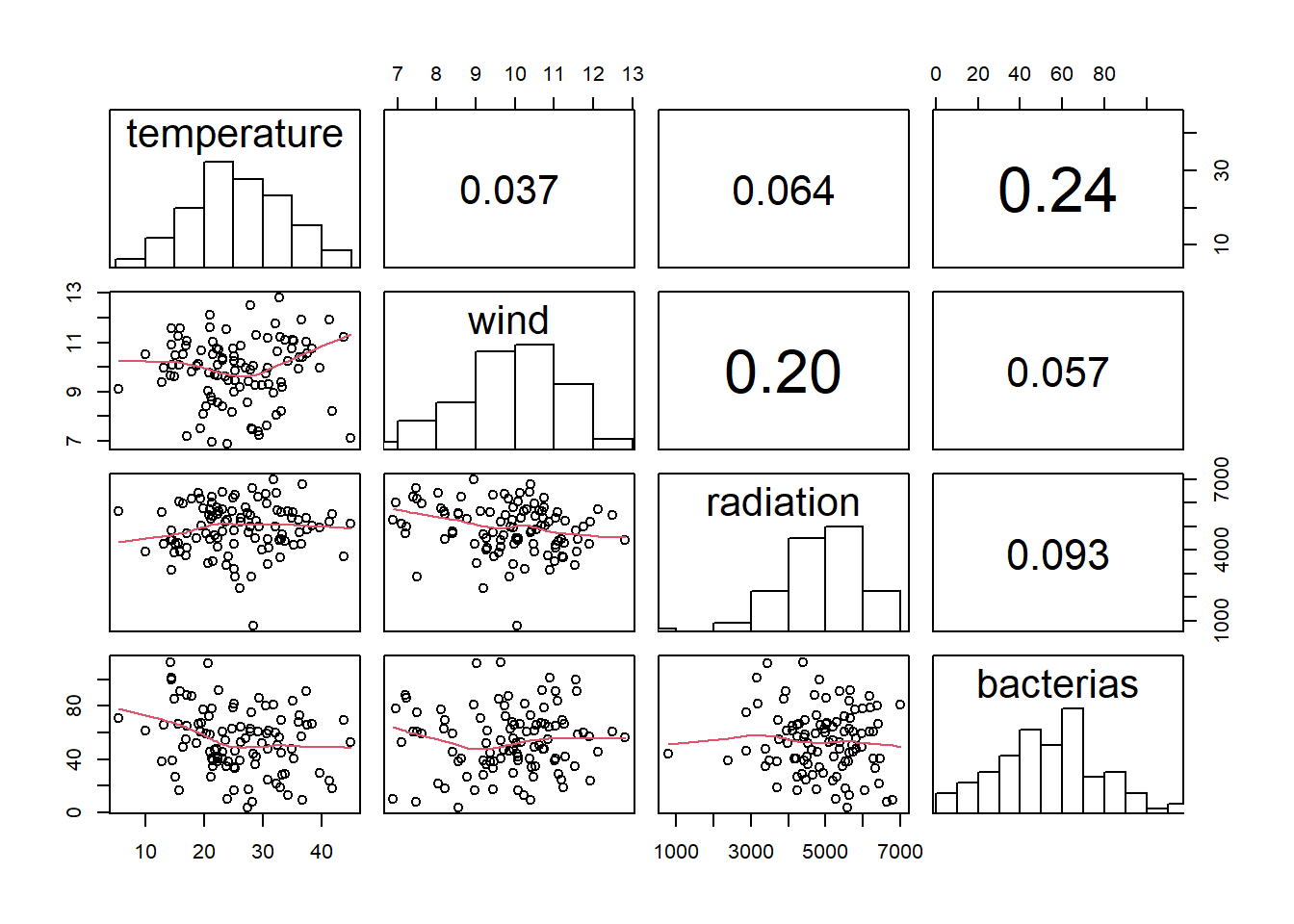

## $ p.value : num 0.8216 0.0627 0.0201Correlations, histograms, and scatters plot modifications

Here, there is a function to get correlations, scatter plots, and histograms with text over the bins.

panel.cor <- function(x, y, digits = 2, prefix = "", cex.cor, ...) {

usr <- par("usr")

on.exit(par(usr))

par(usr = c(0, 1, 0, 1))

r <- abs(cor(x, y, use = "complete.obs",method = "pearson"))

txt <- format(c(r, 0.123456789), digits = digits)[1]

txt <- paste(prefix, txt, sep = "")

if (missing(cex.cor)) cex.cor <- 0.8/strwidth(txt)

text(0.5, 0.5, txt, cex = cex.cor * (1 + r) / 2)

}

panel.hist <- function(x, ...) {

usr <- par("usr")

on.exit(par(usr))

par(usr = c(usr[1:2], 0, 1.5) )

h <- hist(x, plot = FALSE)

breaks <- h$breaks

nB <- length(breaks)

y <- h$counts

y <- y/max(y)

rect(breaks[-nB], 0, breaks[-1], y, col = "white", ...)

}

df %>% # your data frame

dplyr::select(-groups) %>% #remove categorical variables names or numbers if multiple -c()

pairs(

upper.panel = panel.cor,

diag.panel = panel.hist,

lower.panel = panel.smooth

)

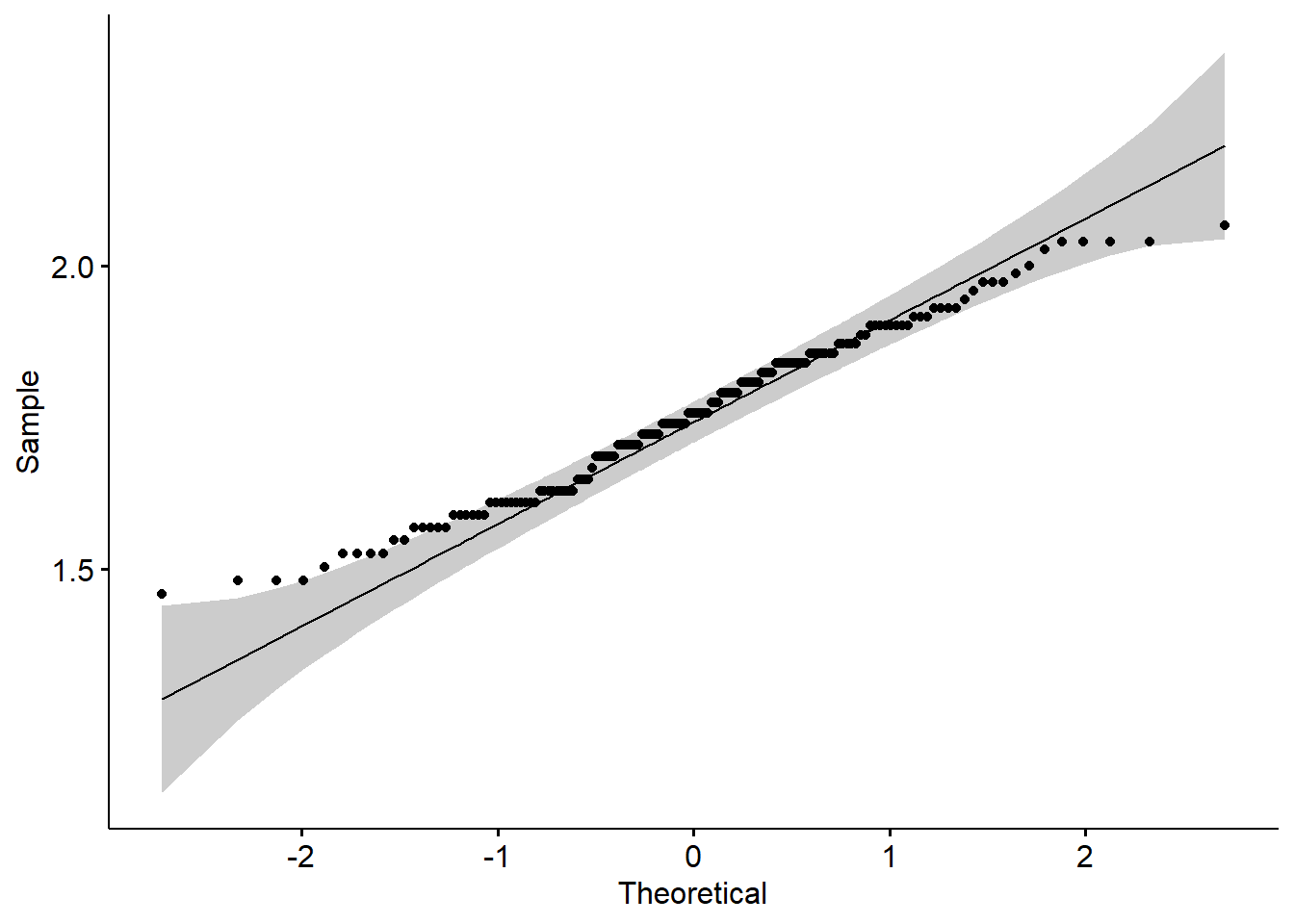

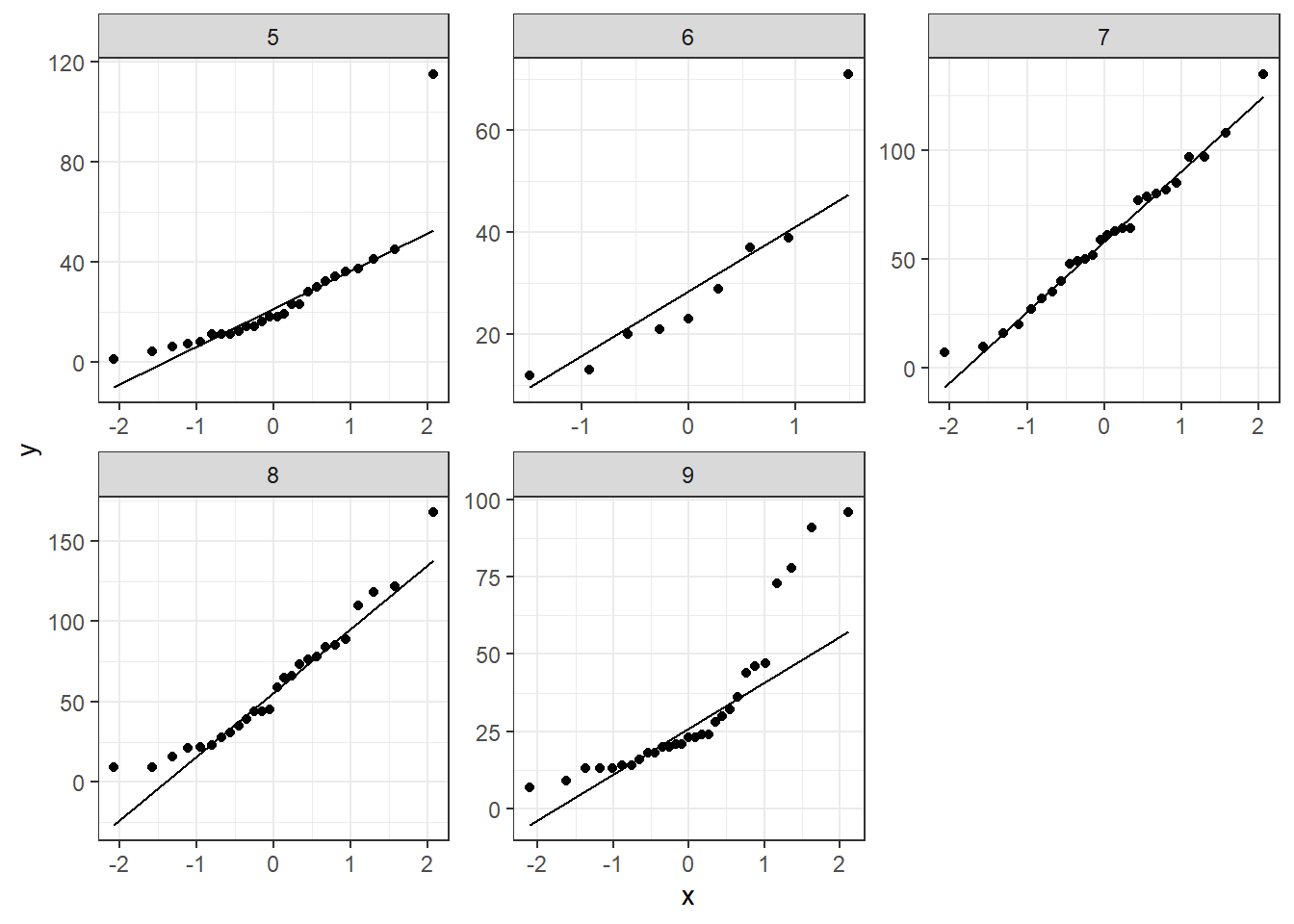

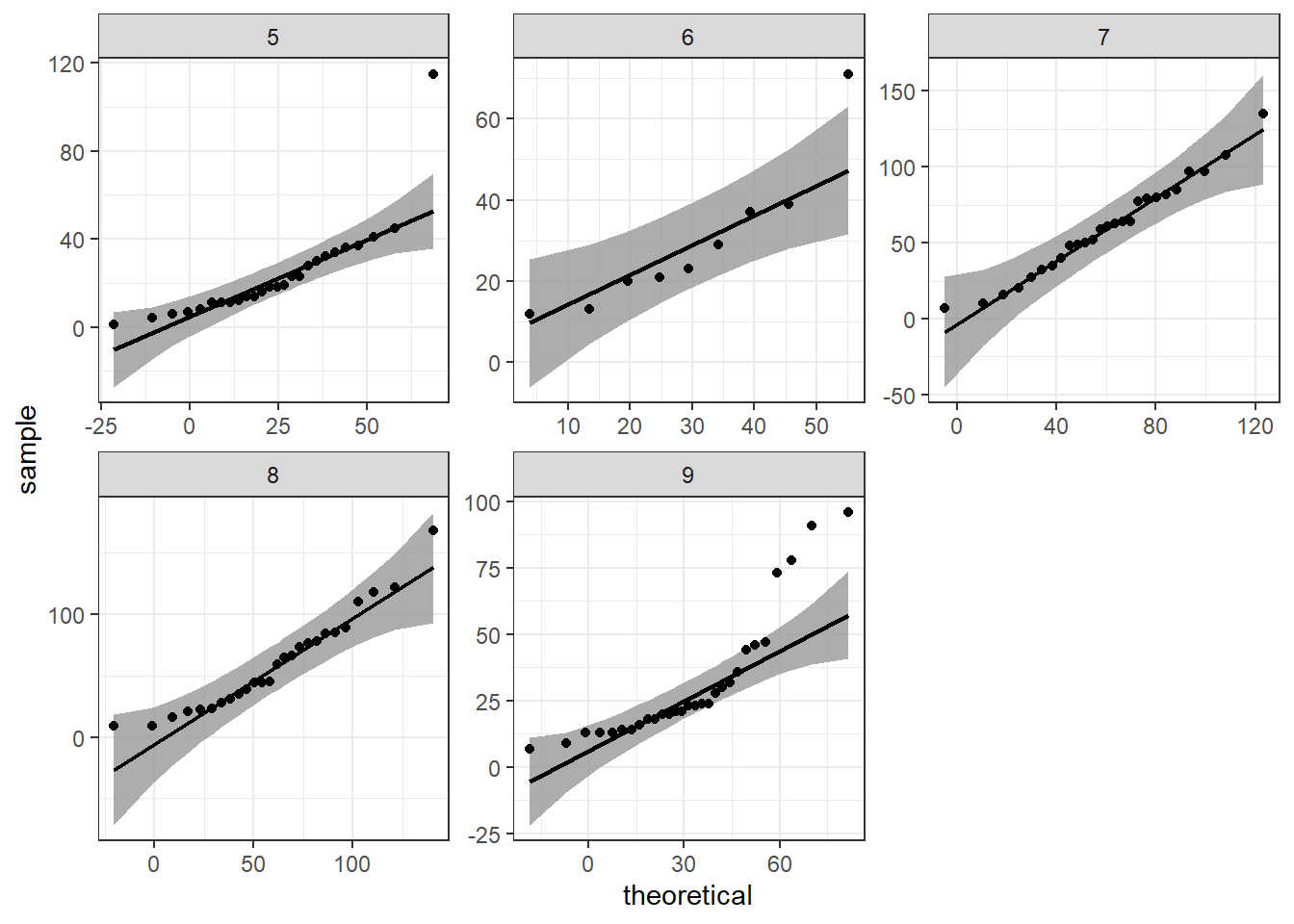

Alternative qqplots

ggpurb adds a confidence region with the qqplot, we can do that with ggplot2 and the package qqplotr

library(qqplotr) #install.packages("qqplotr")

ggplot(data=airquality,mapping = aes(sample=Ozone))+

geom_qq()+

geom_qq_line()+

facet_wrap(.~Month,scales = "free")+

theme_bw()

ggplot(data=airquality,mapping = aes(sample=Ozone))+

#geom_qq()+

stat_qq_band()+

stat_qq_line()+

stat_qq_point()+

facet_wrap(.~Month,scales = "free")+

theme_bw()

#values should be inside that grey shadow

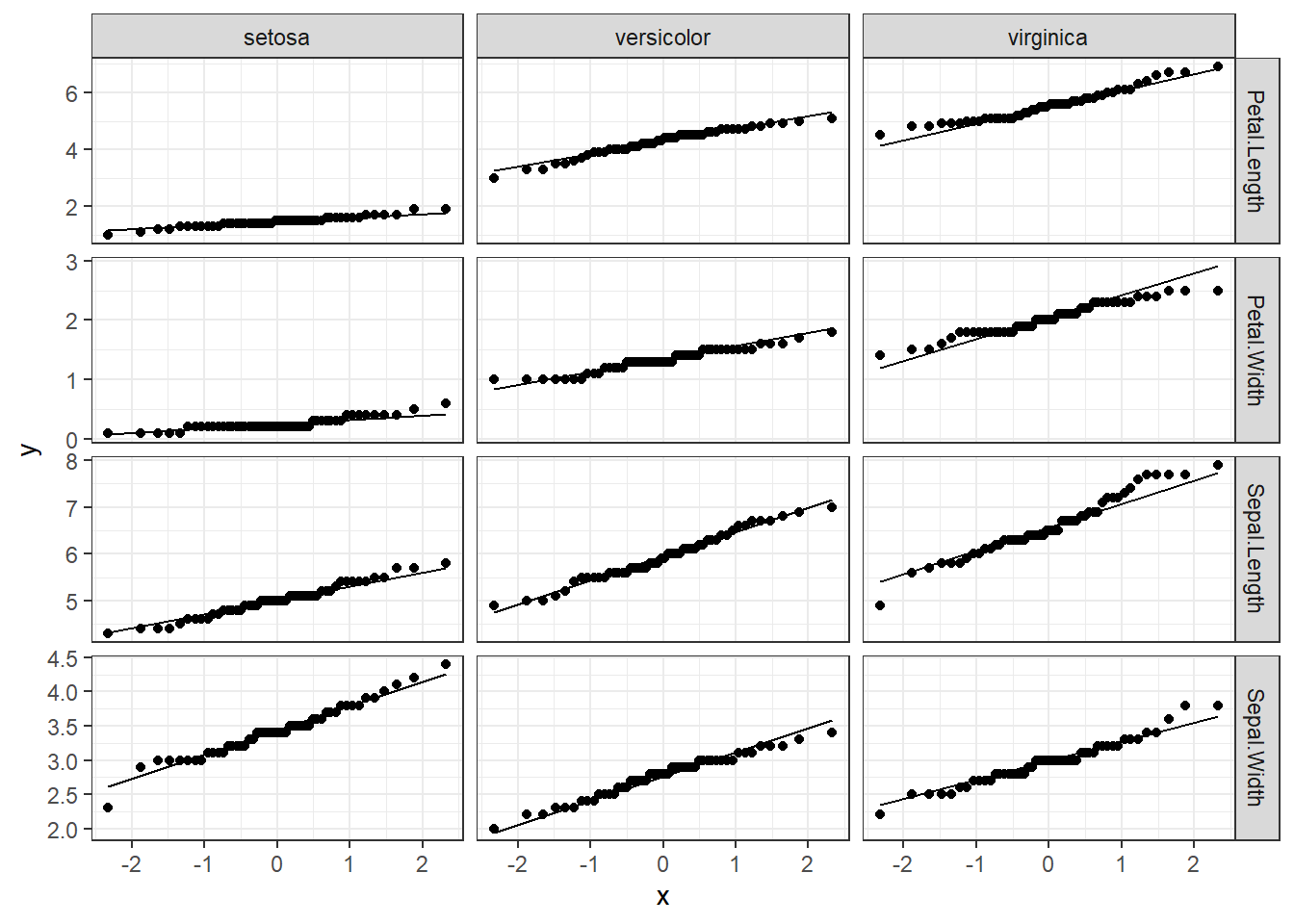

Rearrange multiple variables for ggplot2

To use ggplot2 at a more advanced level, you need to set a long data format. This means that all your response variables need to be in rows and any grouping in a different variable.

Let’s use the iris dataset once again.

head(iris)

## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

## 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa

## 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa

## 5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa

## 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa

iris.long<-tidyr::gather(data=iris,key="Response_variable",value="observation_value",1:4) #the numbers represent the columns that you want to make rows.

# lets bring the code from the first graph and change the variables and the data set

ggplot(data=iris.long,mapping = aes(sample=observation_value))+

geom_qq()+

geom_qq_line()+

facet_grid(Response_variable~Species,scales = "free")+ #y~x

theme_bw()

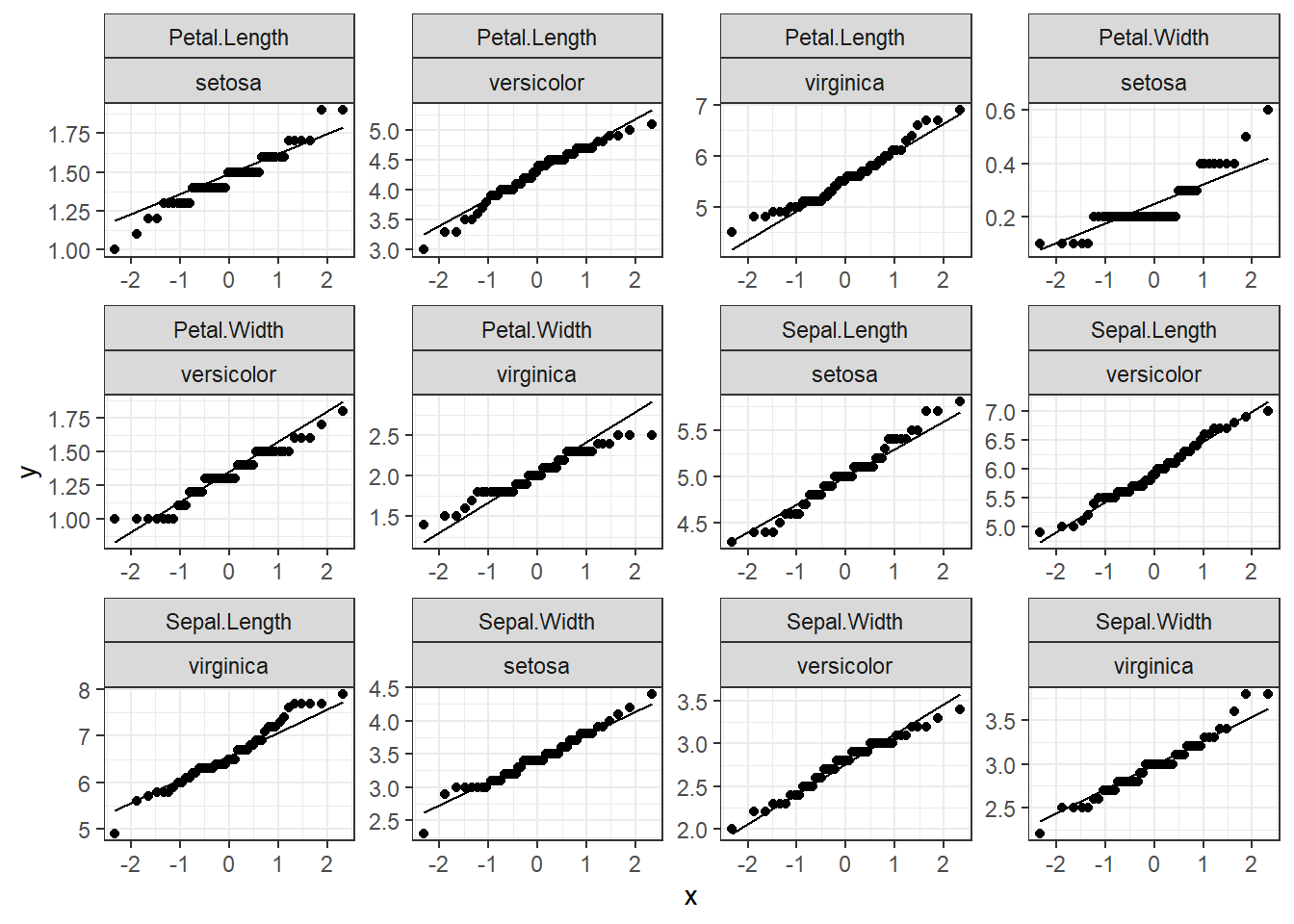

# we got two options for the facets grid and wrap so let's try facet_wrap to see the differences

ggplot(data=iris.long,mapping = aes(sample=observation_value))+

geom_qq()+

geom_qq_line()+

facet_wrap(Response_variable~Species,scales = "free")+ #y~x

theme_bw()

That is a great and fast way to see distributions, and you can create many plots at once.